Let The Choir Sing

About that time I tried to make a grief chatbot, AI anxiety, Wales, coal, Madonna, and immortality

For about four days in 2023, I became obsessed with developing a custom chatbot. I cannot code. I had no business attempting to program anything. I did have access to ChatGPT-4 Plus, and perhaps more importantly I had just been rendered delusional with grief.

What happened was, my best friend died. It was by suicide, which compounded my anguish. I couldn’t talk to him at all anymore, which meant I couldn’t ask him what the hell he was thinking, why he did it, how I had completely missed the signs. Had there been signs? In the absence of any answers, my brain ran on a constant loop, reexamining my memories, looking for the moment I should have figured it out, the moment where I could have somehow stopped it from happening. I kept scouring our old text messages for clues.

I wrote “him” multiple emails each day, sent to an old address of mine, because of this phantom need I had to keep talking to him. Monologue was the next best thing to dialogue.

It didn’t make sense to me that he would never reply. The digital record of our conversations had become a relic, a museum artifact, and also, in a way, it was my friend. It was all I had left of him.

There were fifteen years of messages to wade through. Because we’d lived across the country from each other for decades, nearly all of our conversations had been preserved. We talked about crosswords 36 times. Books 131 times. Elections 28 times. Between the two of us we mentioned anxiety 24 times, sometimes in the context of elections but sometimes just in general.

I could use Ctrl+F to find anything we’d ever talked about, but I couldn’t find the one thing I really needed to know. Nothing in those messages could absolve me of my failure to save my friend.

If you follow me on LinkedIn, or you’ve had the misfortune of talking to me at a party lately, you know my AI anxiety has reached an all-time high.

Countless techbros, in the gender neutral sense, have accused me, either directly or implicitly, of not understanding AI. I’m too lazy or stubborn or scared to learn about it; I’m an ostrich; I’ll be outpaced, left behind; I’m a technophobe, or a Luddite. (I actually consider being called a Luddite to be high praise.)

I promise: I get it. I just don’t like it.

I think LLMs are like Joey Donner from 10 Things I Hate About You: Slick! Attractive, to some people! Toxic! Will absolutely draw a dick on your face if you’re not looking.

The best way I can explain my reasoning for sharing this chatbot story is through the lens of Kat and Bianca Stratford:

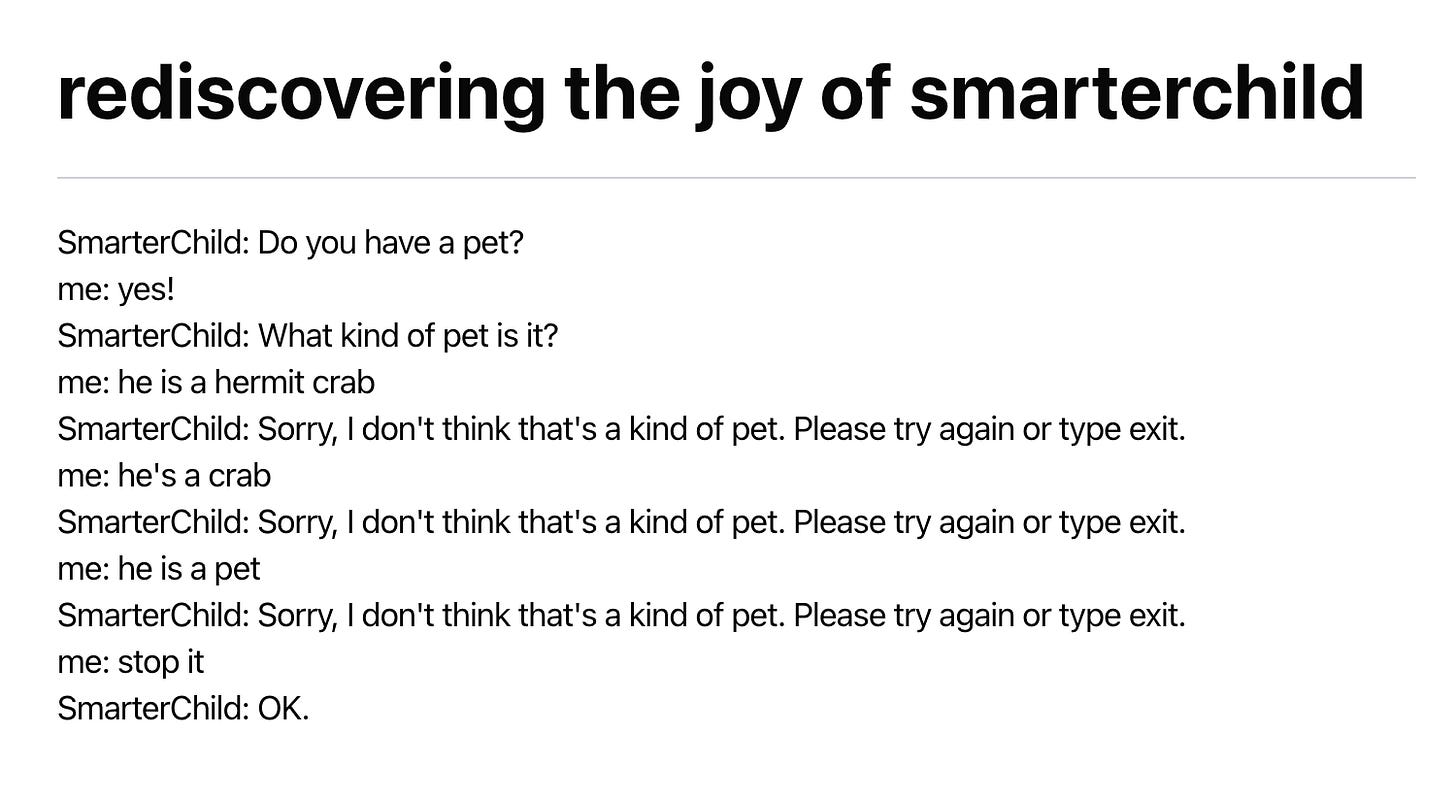

Two years ago, I was willing to believe that ChatGPT was, like, such a babe. I thought of it as a slightly more complex version of SmarterChild, the AIM chatbot experiment I loved tormenting in the late 90s.

I prompted ChatGPT to write a scene from Back to the Future in which Marty has explosive diarrhea, which delighted my kids. I asked Dall-E to make weird, surrealist images to laugh about with my friends. At the behest of a freelance client, I played around with a program that helped generate headlines for the blog posts she paid me to write.

The more I learned about the practices powering applications like ChatGPT, the less I wanted to use them. The theft, the environmental destruction, the human displacement, the impact on employment. The cognitive decline. The deepfakes. The scams. The suicides.

There’s a moral calculus to every decision we have to make. It’s impossible to be perfect; we’re all just doing our best. (I have weird feelings about continuing to use Substack, for example.)

One could argue that the benefits of various AI-powered applications, compared with any one of those disturbing factors, outweigh the risks.

But the compounding of all these factors, paired with the precariousness of late stage capitalism, began to scare me. Without having words for it, I started to see generative AI not as “just a tool,” like so many gender-neutral techbros on LinkedIn insist it is, but as a power system. Or, as Mandy Brown recently put it, an ideology.

What AI is is an ideology—a system of ideas that has swept up not only the tech industry but huge parts of government on both sides of the aisle, a supermajority of everyone with assets in the millions and up, and a seemingly growing sector of the journalism class. The ideology itself is nothing new—it is the age-old system of supremacy, granting care and comfort to some while relegating others to servitude and penury—but the wrappings have been updated for the late capital, late digital age, a gaudy new cloak for today’s would-be emperors.

The ideology, or more accurately a cluster of ideologies, has a name: TESCREAL. It’s an acronym coined by Émile P. Torres and Timnit Gebru, two prominent AI ethicists who have, in the past, been affiliated with the ideology. They now know how dangerous it is. (In fact, I was working at Google when they fired Gebru for calling attention to some of the harms inherent to Google’s own AI technology.)

I recommend reading the Truthdig breakdown written by Torres about TESCREALism. It’s terrifying, and long, but important. If I had to distill the whole article down to one excerpt, it would be this one:

Together, these ideologies have given rise to a normative worldview — essentially, a “religion” for atheists — built around a deeply impoverished utopianism crafted almost entirely by affluent white men at elite universities and in Silicon Valley, who now want to impose this vision on the rest of humanity — and they’re succeeding.

In short, some of the minds behind TESCREAL – many of whom, including Sam Altman and Peter Thiel, now have unfettered access to the federal government – subscribe to the radical belief that what happens on Earth today in the service of a future AI-powered utopia doesn’t matter.

The tech overlords believe they will live forever, and rule over us forever, once they upload their consciousness to the cloud. They don’t just want wealth and power now. They want it forever. And I haven’t even gotten into the Curtis Yarvin of it all.

It sounds like science fiction, but it’s real.

It’s also why these science-pilled atheists have aligned so tightly with the Christian right. Both groups care more about a hypothetical utopian future – whether that’s tech based, or religious – than anything happening on Earth today.

Any suffering that comes while they pursue this future is just collateral damage.

[Edited to add: The new HBO film Mountainhead demonstrates this ideology and its dangers beautifully.]

My friend and I discussed AI a bunch of times over the years, usually in a jokey way that tap-danced around our anxieties. In 2017 we laughed about a neural network naming paint colors. “I’m partial to Stanky Bean and Hurky White,” I wrote. He liked Gray Pubic.

About six months before he died we chatted about Michelle Huang’s psychological experiment, in which she trained an AI chatbot on her old journal entries so she could have a conversation with her inner child.

Me: What a time to be alive! Or dead, I guess.

Him: 😆

Me: How long do you think until someone starts a company that feeds your dead loved ones’ written material into a chatbot so you can keep “talking” to them?”

Him: In the pitch: “at no point in history have there ever been more dead people”

Me: Market cap: ∞

I put down my phone and thought about Michelle Huang and her inner child. I thought about Vauhini Vara’s gorgeous, moving attempts to write about her dead sister with ChatGPT. I thought about the Dadbot guy and the woman who created a chatbot of her dead best friend. There was precedent for this, right?

I decided I would try to do it: I would train a chatbot on our text exchanges, so I could keep talking to my friend forever.

It seemed the obvious thing to do.

I’m trying my best not to use the term “AI” as a catch-all term here. First of all, it’s essentially meaningless, a marketing term attempting to neatly encompass a sprawling ideology.

When I talk about LLMs, large language models, I mean conversational interfaces that have been trained on mass quantities of (mostly stolen) data, like Claude and ChatGPT.

When I talk about generative AI, I mean technology that encompasses LLMs but might also include Midjourney or Google’s Veo3. Technology that doesn’t just answer questions, but responds to text inputs by creating non-textual outputs like images, video, or sound.

AI can do lots of other things. Much of it would pass the moral calculus test. Karen Hao, the author of “Empire of AI,” has written a vital op-ed in the New York Times about the dangers of AI in the hands of authoritarianism. She shares a glimpse of what a better future might look like:

Technological progress does not require businesses to operate like empires. Some of the most impactful A.I. advancements came not from tech behemoths racing to recreate human levels of intelligence, but from the development of relatively inexpensive, energy-efficient models to tackle specific tasks such as weather forecasting. DeepMind’s AlphaFold built a nongenerative A.I. model that predicts protein structures from their sequences — a function critical to drug discovery and understanding disease. Its creators were awarded the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

When we talk about “AI” as a blanket term, we’re grouping this benevolent technology with the nefarious. It’s a disservice to the people who are using it to cure cancer, and it gives undeserved credit to people like Sam Altman.

I would never tell you not to use AI, because I’d be a hypocrite. I use AI all the time, in ways that may or may not be ethical, but that I have decided benefit me enough to continue. I have no idea if this is the right move in the long run, but I am happy to benefit from advances in cancer research. I frequently ask Google Images to find a photo for me using facial recognition. My beloved Merlin app helps me to identify birds by their songs.

I will not use LLMs or anything that could be considered generative AI.

I know technology can be used for good – but this only happens with firm regulations that keep the TESCREAList tech bros grounded in ethics.

That’s not what’s happening today. In fact, Trump’s “big, beautiful bill” contains a hidden line item that would ban any regulation of AI technology for the next ten years. Even MTJ thinks it’s bad, and that’s really saying something.

The first problem I ran into in my vibe coding experiment was ChatGPT itself. It cautioned me that building my chatbot might be unethical. It reminded me that I wouldn't be able to get his consent, nor would this chatbot bring him back. This frustrated me. I didn’t need it to moralize or to judge me. I wanted to talk to my friend again.

In an email to “him” during this four day experiment, I wrote:

The thing is, I'm the other half of that conversation, and you're dead. So, is it unethical? It's certainly unholy. Ghoulish. Creepy. But unethical? I don't know. What's the worst that could happen? I spend all day fake chatting with your digital spectre?

I sallied forth. The hardest part was formatting the messages in a way that could be parsed by an LLM. I downloaded an app that promised to turn our text messages into rows on a spreadsheet, but it took days to process the data, and the output was nearly incomprehensible.

By the time I’d spent hours attempting to reformat the spreadsheets, the delusion passed, like a fever.

Not long after my friend died, my dear friend July gifted me a copy of the book The Long Field, by Pamela Petro. I finally started reading it a few months ago. It’s about the author’s love affair with Wales, and with the Welsh concept of hiraeth (pronounced HERE-eyeth). Hiraeth roughly translates to a sense of yearning for a place you’ve never been; it’s a feeling associated with, as Petro writes, the “presence of absence.”

The book is not exactly about grief, but it’s not not about grief.

It’s a beautiful, sprawling narrative that weaves together Petro’s own experience with Welsh history and culture. In one chapter, she writes about the Welsh coal miners strike in the 1980s. The miners unionized, showing remarkable solidarity in protesting Margaret Thatcher’s attempts to privatize the coal industry.

This chapter minded me of an insightful essay I read comparing ChatGPT to balloons and I thought, well, maybe it’s more like coal.

It will transform everything.

We will never be able to say whether it brought more harm than good.

The very people who suffer the most from its effects will be the ones who insist on its importance.

By the time we realize its harms, it might be too late.

In The Long Field, Petro revisits some of the Welsh mining towns most impacted by the closures of the coal mines. Despite their best efforts to fight back, they lost the battle back in the 1980s – to Thatcher, but also to progress. Today there is only one active coal mine in all of Wales.

Most of the surviving miners say they miss it – that, given the opportunity, they’d go back to the mines tomorrow. Toward the end of the chapter, she witnesses a men’s choir singing a Welsh hymn. She writes that the words of the song don’t matter so much as the “uncanny, lovely noise they make when sung simultaneously by scores of men.”

She writes: “A choir is one step away from a strike.”

Once I’d given up on creating the chatbot, I had to contend with the actual grief I’d been keeping at bay. To some degree, I knew this would happen. I won’t bore you with the play by play here. Suffice it to say, the grief flattened me.

What helped the most, in the end, was that several friends of mine opened up to me about their own experiences with suicidal ideation. Real, live, human friends, taking a leap, diving in with generosity and vulnerability to help me understand how they thought about and dealt with the allure of death. How they clawed their way out of it.

These friends helped my brain to stop spiraling around the question of why. They didn’t have the answers, but their stories showed me that there was no why.

There would never be an answer, no matter how hard I looked, no matter how many memories I scoured. And maybe that was okay.

A few weeks ago, another friend of mine asked how I was handling the loss of my dead friend, two years later. “Well,” I quipped. “He’s still dead.”

“Or maybe he’s more alive than he ever was,” my living friend replied. He meant this as a comfort, I knew, but it made me throw back my head and laugh.

“If he found himself in an afterlife he’d be so pissed,” I said, when I’d recovered. “After going through all that effort to stop living, only to find he has to do it forever?”

Belatedly, there was my answer about how my friend would have felt about being resurrected as a chatbot.

I don’t believe in God, or an afterlife, and neither did my friend. I find great comfort in this. I would like my life to end in nothingness, when I’m good and ready to go.

But if it doesn’t, if there is some kind of afterlife, I don’t want it to manufactured by the same people who made life on earth a living Hell for so many people. I don’t want to live forever in Elon Musk’s Spiritual Paradise™ for the low price of $9.99/month times infinity. No thank you.

The other day I was driving and listening to Like A Prayer.

I know the song draws parallels between religious rapture and sexual bliss. But in that moment, listening to the literal choir sing behind Madonna’s clear vocals, I thought about Pamela Petro and the coal miners.

A choir is one step away from a strike.

In the The Long Field, Petro describes the concept of solastalgia as “something like being aware that the place you live in and love is under immediate threat.”

That resonated.

Petro visits a former mining town called Aberfan. In 1966, a slag heap gave way in the town, swallowing nineteen houses, 168 children and 28 adults.

She writes about the residents of Aberfan today:

To accept the loss, the sadness of their deaths, and then to fiercely turn around and call this place home, to honor it with remembrance, is to embrace the anger and protest embedded in all solastalgic hiraeth. Because in that protest is an embrace of Otherness, of the home of the Other on the far side of Power. And like speaking Welsh, that’s always a political act.

Things feel really, really bad right now. I feel powerless, like there is nothing I can do to stop the march of authoritarianism straight into fascism.

What I can do, and what you can do too, is to pick a way to quietly resist – ideally with other people. Form your choir, your union, your squad, whatever that looks like to you.

For me, it’s spending less time on social media and more time with the people I love. Getting involved in hyperlocal politics. Creating, as much as I can, even when it’s stupid. Especially when it’s stupid.

I am learning to live without answers – without asking ChatGPT – and I think this, too, is a form of resistance.

Delights

Let’s bring back delights, shall we?

My dear friend July’s gorgeous poetry epic, moon moon, which just came out last month

My dear friend Veena’s gorgeous memoir, The True Happiness Company, which chronicles her time getting into, and out of, a cult, and came out, improbably, on the same day as July’s book

Leif Enger’s latest novel, I Cheerfully Refuse, which somehow manages to be bleak and heartbreaking and beautiful and hopeful all at once.

The fact that my random shower thought about AI and cocaine has gone mini viral on LinkedIn, when none of my earnest appeals have come anywhere close

Happy weekend, friends.

This is a wonderful and insightful post on grief and so much more. I'm sorry for the tragic loss of your friend - there really is no why, only the "IFs" remain. AI - I've not used it and don't see the benefit to me at this point in my life. A friend who is a graphic designer just returned from Senegal where she was part of an workshop to teach how to use AI for children's book illustrations. The illustrations were beautiful and she had an amazing experience, I still wonder how it will help them. The cost of using an illustrator is more expensive of course, but does that mean that they'll just churn out more books (possibly subpar like the fashion industry when you have cheap labor) and less illustrators will have a job? AND the AI/cocaine post is truly eye-opening! Kudos to you Natalie!

I loved reading this. Thank you for sharing the inner workings of your brain and heart. Also the AI/cocaine thing is, well. *Chef's kiss.*