Aut Zuck Aut Nihil

Or: chaos is a ladder

It’s been almost nine years since I left my job at Meta, and I really thought I had managed to separate my identity from the company’s. But Meta’s recent policy and product decisions, paired with Zuck’s enthusiastic participation in Trump’s inauguration, have forced me to realize I am still processing information about the company in an unhealthy way. I can’t stop asking myself what went wrong.

I think I’ve figured something out, something that probably should have been obvious to me all along, and that’s what I want to talk about today. We have to go back – to 2020, but also 2006, and 1962 and 1885 and 1440 and even 286 A.D. It’ll take me a little while to get there, and I hope you’ll bear with me.

The Authority Vacuum

In June of 2020, I joined a group of my former coworkers to write an open letter to our former boss, expressing our dismay at some of the company’s policy decisions around Trump, and his spread of misinformation on the platform.

We wrote the letter collaboratively, on late night Zoom calls and in the comments of a shared Google doc. While we worked, I felt a kind of homesickness for the early days at Facebook. I missed the energy that came from collaborating with good, smart people, and the feeling of creating something new together. Most of those coworkers and I met while working at Facebook’s headquarters in 2006, back when we still believed we were changing the world for the better. At the time, I told my parents I had finally found my people: the “cool nerds.” It was one of the happiest times of my life.

When we wrote that letter, I kept asking myself: Where were all the good, smart people at the company? What changed?

The theory I eventually developed was pretty simple. In Facebook’s quest to “make the world more open and connected,” it succeeded in empowering individuals, but accidentally eroded the very notion of an authority – not just the notion of an objective truth, but the notion that any established institution could help us to understand truth. We underestimated bad actors, and the ways people would game the system to create discord and chaos – the way Russia may have used social media accounts to sow disinformation and reap discord, for example. This led to what I think of as an “authority vacuum,” like the power vacuums that appear when a government experiences a sudden loss of power with no viable alternative installed in its place.

The effect is nearly always destabilizing. Warring factions tend to emerge. Dictators materialize. (The Iraq War comes to mind.) The internet feels like a civil war, I reasoned, because it is one; Facebook toppled established systems of authority without creating any viable alternative to them, and in the absence of authority people began attacking and policing one another. It’s no surprise half the country craved an authoritarian leader, a tough daddy to tell us all what to do.

I believed the theory was solid, but I couldn’t write coherently about it. The essay kept collapsing on itself, like a poorly made vase on a pottery wheel. Eventually I gave up.

I started thinking about that theory again during Trump’s second inauguration. A few days into his second term, my mom dropped off a box of things from her attic. An American flag with 48 stars from her childhood; a pamphlet about the moon landing; an book report she’d written in fifth grade. In the box there was a copy of the New Yorker, from May 2006. It was addressed to my college apartment in Brookline, Massachusetts. I couldn’t figure out why she’d brought it to me, or why she’d kept it all those years, until I leafed through the yellowed pages and found a feature on Mark Zuckerberg. I must have handed it to her as a way to explain my job: I’d been working as an intern at Facebook since the fall of 2005, and in June 2006, shortly after my college graduation, I would move to California to start as a full-time employee.

In the article, which he titled “Me Media,” John Cassidy attempted to describe to New Yorker readers what, exactly, a Mark Zuckerberg was. He did a pretty good job:

In August, 1995, when Netscape issued stock on the Nasdaq and became the first major Internet company to go public, Mark Zuckerberg was about to enter the sixth grade at a middle school in Ardsley, a small town in Westchester County. He had a new desktop computer—a Quantex 486DX with an Intel 486 processing chip—and had bought a book called “C++ for Dummies,” to teach himself how to write software. “I just liked making things,” he recalled recently. “Then I figured out I could make more things if I learned to program.” By the time he finished ninth grade, at Ardsley High, he had designed a computer version of the board game Risk, in which rival forces battle for global domination. Zuckerberg’s game was set in the Roman Empire, which he was studying in Latin class, and featured a virtual general called Julius Caesar, who was such an able military strategist that even Zuckerberg had trouble defeating him.

When I read that paragraph, I thought about the essay I’d tried writing five years ago, and I suddenly realized why it didn’t work. It was because I had gotten something fundamentally wrong.

The dismantling of authority wasn’t an accident; it was the intention all along. The bad actor was always Mark Zuckerberg, hell-bent on amassing power.

The Global Village

In the summer of 2006 I attended my first company-wide meeting at Facebook. I’d just started working full-time at our headquarters in Palo Alto. Ordinarily, we worked out of an office upstairs from a skateboard shop, but on this day we all walked two blocks to sit on the musty velvet folding seats of a local movie theater. We had outgrown all of our conference rooms. We were wearing hoodies and flip flops. Most of us were under 25.

In front of the theater stood a young guy with close-cropped brown hair, wearing a blazer and blue jeans. He held a microphone in one hand and a remote in the other, which controlled the slides projected onto the movie screen behind him. His name was Chris. We all leaned forward when he spoke. Nobody pulled out a BlackBerry. When Chris presented to us, he didn't show us numbers or product mocks or screenshots or bullet points. We looked at pictures.

Chris clicked forward and it was a lithograph of Gutenberg’s printing press. Clicked again and it was a photo of William Randolph Hearst. He clicked again and it was Rupert Murdoch, his jowly face, his wire-rimmed glasses. Chris let his clicker hand fall down to his side and turned to face the room. “Since the dawn of the written word,” he said, gesturing with the remote, “there have been a few old white men who got to decide what the news is. They decided what we read, and watched. They decided who got to have a voice.”

He clicked forward once more, and there was a black and white photograph of a white man resting his chin in his hand. The man in the picture had a mustache and, Chris told us, his name was Marshall McLuhan. I vaguely recognized McLuhan from that one scene in Annie Hall and from a marketing class I took in college. Chris told us he was famous for saying things like the medium is the message and for basically predicting the internet with his notion of the global village.

“That’s what we’re going to change,” said Chris. “When we connect the world - and we’re going to connect the world - everyone will get to have a voice.” My skin prickled into goosebumps.

Before long Facebook made its mission statement public. We were going to make the world more open and connected. We used phrases like “social graph,” and talked about organizing information around people. The idea was that people found their friends more interesting than anything else; therefore, any information filtered through the consciousness of our friends would be more engaging than any other information. It was a way of dealing with the explosion of content the internet created - to make the world more open and connected, yes, but also to make it smaller and more digestible. Or, as McLuhan put it: “The global village is at once as wide as the planet and as small as a little town where everybody is maliciously engaged in poking his nose at everybody else’s business.”

Gutenberg, Mergenthaler, and the Printed Word

Around the time McLuhan published The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man, my grandfather was working as a printer for the New York Times. His job was to operate a machine called the Linotype; he typed the world’s news into this machine every night, which in turn set the words, in reverse, into metal. When inked, the metal would roll again and again onto sheets of newsprint to create the paper.

He loved this work. He loved it so much that he researched, wrote, and published the biography of Ottmar Mergenthaler, the man who invented the original Linotype. Johannes Gutenberg created a way to cast individual letters into metal; the Linotype increased that scale tremendously by casting entire lines of text. In this way a newspaper could generate more than 350 words per hour with virtually no errors, and print the pages even faster.

I have a copy of the biography of Ottmar Mergenthaler inscribed by my grandfather, in his elegant script. I was five years old when it was published in 1989, but he addressed it to me along with my parents. The inscription reads, “Among other things, life should be a series of contributions to make the world more knowledgeable. You are, and will be doing, your share. This is how I am helping. With love, Dad and Grandpa.”

In my work at Facebook, as a lowly sales planner, I believed I was contributing to make the world more knowledgeable. I think my grandfather agreed, although he had trouble understanding the Internet and what Facebook was. Over the years, he would clip out articles from the Times whenever they mentioned Facebook. He mailed them to me, or handed them to me tucked into manila folders whenever I’d visit him.

September, 2006. Yahoo Woos a Social Networking Site. Features a fish-eye lens photo taken of Mark Zuckerberg sitting cross-legged on a desk in our open-plan office. Out of focus behind him you can see me, in a blue t-shirt and Rainbow flip flops, hunched over my desk.

November, 2007. Facebook to Turn Users into Endorsers. Quotes Mark Zuckerberg: “Nothing influences a person more than the recommendation of a trusted friend.”

September, 2008. Brave New World of Digital Intimacy. Quotes Mark again: “Facebook has always tried to push the envelope,” he said. “And at times that means stretching people and getting them to be comfortable with things they aren’t yet comfortable with. A lot of this is just social norms catching up with what technology is capable of.”

March, 2009. Is Facebook Growing Up Too Fast?

The Roman Empire

In those early days of Facebook, Mark famously lived very simply, in a sparse room with a mattress on the floor. He drove a modest car, wore a hoodie and Adidas sandals every day. As Facebook grew, I’d hear friends and commentators talk about how we only cared about money. I would vehemently disagree.

I worked on the ad sales team, and it constantly felt like we were fighting to get the resources we needed to build a thriving business. Mark’s approach toward advertisers and, it seemed, money bordered on disdainful. Ads were something to tolerate, not to center; revenue was an afterthought, a way to pay the bills while we worked to achieve his vision.

I think I was right that Mark never really cared about money. What I didn’t realize was how focused he was on power, even though we frequently joked about “world domination” in staff meetings. I’m only now realizing he wasn’t joking.

Over the years, Mark has spoken publicly about his fascination with the Roman empire; he famously named all three of his daughters after Roman emperors. In 2018, when the New Yorker published another feature on Facebook, they called it “Can Mark Zuckerberg Fix Facebook Before It Breaks Democracy?” In the article, Evan Osnos quoted Mark talking again about the Roman empire.

Zuckerberg told me, “You have all these good and bad and complex figures. I think Augustus is one of the most fascinating. Basically, through a really harsh approach, he established two hundred years of world peace.” For non-classics majors: Augustus Caesar, born in 63 B.C., staked his claim to power at the age of eighteen and turned Rome from a republic into an empire by conquering Egypt, northern Spain, and large parts of central Europe. He also eliminated political opponents, banished his daughter for promiscuity, and was suspected of arranging the execution of his grandson.

Osnos concluded with his own analysis of the company’s policy decisions.

The caricature of Zuckerberg is that of an automaton with little regard for the human dimensions of his work. The truth is something else: he decided long ago that no historical change is painless. Like Augustus, he is at peace with his trade-offs. Between speech and truth, he chose speech. Between speed and perfection, he chose speed. Between scale and safety, he chose scale.

At the time, I agreed with the take, and with its assumption that Meta was trying to do good, despite complex philosophical and technical challenges. I felt this way for a long time. When I talked to friends who’d left the company, we sometimes talked about the posters that lined the walls of the office. They read "MOVE FAST AND BREAK THINGS,” persimmon red, all caps.

“I didn’t realize we’d move so fast we’d break democracy,” I’d say, and we’d all nod remorsefully.

It wasn’t until my mom dropped off that yellowed New Yorker that I realized: there was never an intent to do good. The intent, I now believe, was always to break democracy, but to do it in a way that he wouldn’t get caught. As Littlefinger famously tells Varys in Game of Thrones, chaos is a ladder.

My mistake was assuming Mark intended to build a product that made the world more cohesive, not more divisive.

Mark’s mistake has been to model himself after the first Roman emperor, when in reality he has more in common with the last.

Pop Quiz

Q: What was one of the earliest power vacuums in human history?

A: The fall of the Roman empire.

Q: What followed?

A: The Dark Ages.

What now?

I always like to end with something pragmatic, or uplifting. I’m not sure I can do either today, but I can tell you what I’m doing to manage this.

I have finally stopped using Instagram and Facebook. I don’t know for how long. It’s too late for this to have any impact on Mark’s path to world domination and destruction. But it’s not too late for me to prioritize my own mental health, and opening up social media makes me feel bad. (Kelly Stonelake and Brian Boland have both written about this better than I could.)

I’m trying to read news written by journalists, without filtering the news through the people I know, or the people I pretend I know because I follow them on social media.

I’m still reading the New York Times, which is deeply flawed but still committed to journalistic principles in ways other papers are not.

I’m reading Tangle News, which offers a 360 degree view of U.S. Politics, clearly framing arguments from the left and the right.

And I’m still reading Substack, although it’s quickly becoming enshittified; I’m trying my best to avoid Notes and focus only on newsletters.

I’m focusing on hyperlocal solutions: my town’s government, and mutual aid.

I’m reading books before bed, instead of the news.

I’m doing my darnedest to avoid interacting with any GenAI systems, which I believe are the next rung on the chaos ladder that leads to destruction and the next Dark Age.

These tactics, combined with the miracle of modern medicine, have helped me to feel somehow more stable – they are rungs on a ladder up and out of despair. I don’t know where it leads.

I’ll leave you with this.

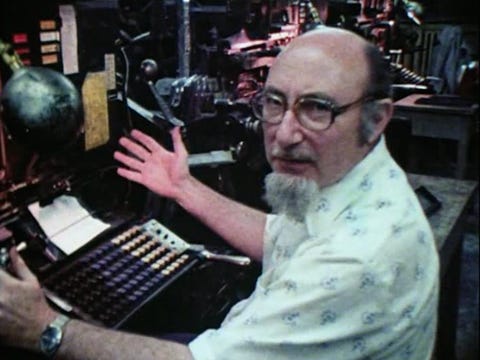

Toward the end of his life, my grandfather was featured in a documentary film about the rise and fall of the Linotype machine. In the documentary he’s wearing a camel-colored wool cardigan and sitting on the couch in his living room, facing the camera.

“I spent thirty-five years working for the New York Times,” he says. “And that was - that was my life.” He chuckles a little bit here. The background is pleasantly out of focus but I can make out his record player behind him. The Zanzibar chest at the base of the stairs.

“I guess I was just built for that type of work, and the other people were as well. They didn’t think much about it, maybe it was just a night’s work to them. But I was maybe more sensitive and I could see this was a story every night, the story of our lives, the story of the world’s life. The world is being made new for tomorrow.”

I work in making print newspapers and the process makes me happy. Every night we rush to get the papers out to the trucks; the rush is just culture now because the news in them are already old. But every day it makes me happy. Stories written down and set in ink, curated and written by real people, even typos unable to be changed later. Context always clear; name of the publicaton, a date, a first page and the last. Enough news for one day for one mind. More news to follow tomorrow.

I love the internet, and I love the interesting stories I get to read like this one. Thank you for writing it. Maybe the dark ages are upon us. We'll have to move slow and fix things for a while.

The tragic thing about these oligarchs is that they really think they're doing the right thing. They think the world will teeter into chaos unless they alone control the reins. The idolization of Augustus is perfectly revealing of their psychosis: they believe they are saving humanity, which is terrifying because it will allow them to justify any manner of awful things, when they believe in such a righteous crusade.